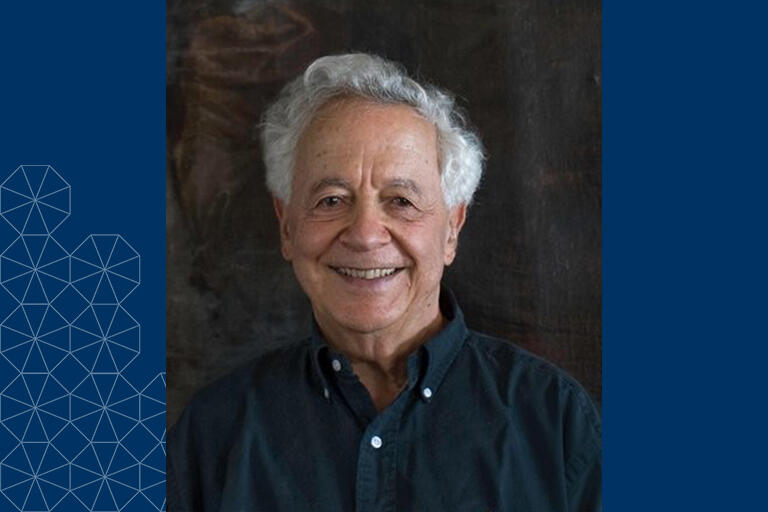

Professor Guy Benveniste, known for his work in organizational theory and the politics of expertise, is remembered by Berkeley School of Education alums and colleagues as an extraordinary teacher and mentor. He was a respected academic who enjoyed a lifelong interest in art, good food, and stimulating conversation alongside his scholarship.

Benveniste died on December 3, 2022, at the age of 95.

“He was one of my favorite people in the School of Education at Berkeley,” said Marge Plecki, who earned her PhD at BSE (then Graduate School of Education or GSE) in 1991 and recently retired from being a professor at the University of Washington School of Education. “He was very egalitarian in making sure he set up an environment where people learned in their own way.”

Plecki remembered how Benveniste’s face would light up when he could engage his students in debates, analyzing their claims and asking how they could back them up. When she walked down the hall in the school’s former site in Tolman Hall while in graduate school in the late 1980s, she said Benveniste would always be interested in what she was doing, asking, “What are you up to?”

“He could relate to other people’s interests, make connections with the literature and scholarship, and think in deep ways,” Plecki said.

Former BSE Dean Judith Warren Little, who led the school between 2010 and 2015, met Benveniste when she was applying for a job as a professor in 1987. She felt supported by Benveniste from the moment she first met him in Tolman Hall, describing him as scholar whose work offered important insights for her own research but who was also a warm and generous colleague. “He always had a twinkle in his eye,” said Little.

BSE alum Donna Kay LeCzel (1992) echoed the sentiment. “Guy did have a twinkle in his eye. He never took himself too seriously,” LeCzel said. “He was always able to bring some bit of fun or humor into every teaching and learning opportunity."

LeCzel first met Benveniste during a class in organizational theory in the first years of graduate school. She recalls that Benveniste’s class moved around Tolman to different rooms in the building, and on one day a sign directed students to a downstairs classroom. When they entered the classroom, the students found Benveniste lying flat on his back atop a desk.

“He said, ‘I’m fine but my back’s not. So take a seat and we’ll proceed,’” LeCzel recalls with a laugh. Benveniste — who apparently enjoyed teaching so much he didn’t want to miss a class due to back pain — taught the entire class from his prone position.

LeCzel described Benveniste as a mentor who, along with anthropology Professor John Ogbu, helped her prepare for the international work in teacher development and organizational development she did for many years following her graduation. She kept in touch with Benveniste as she conducted research around the world in places like Botswana, Lesotho, Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Nigeria. She said Benveniste’s international perspective was outside the norm and it’s “what made him such a wonderful mentor for me.”

Snapshots of Benveniste’s path to Berkeley

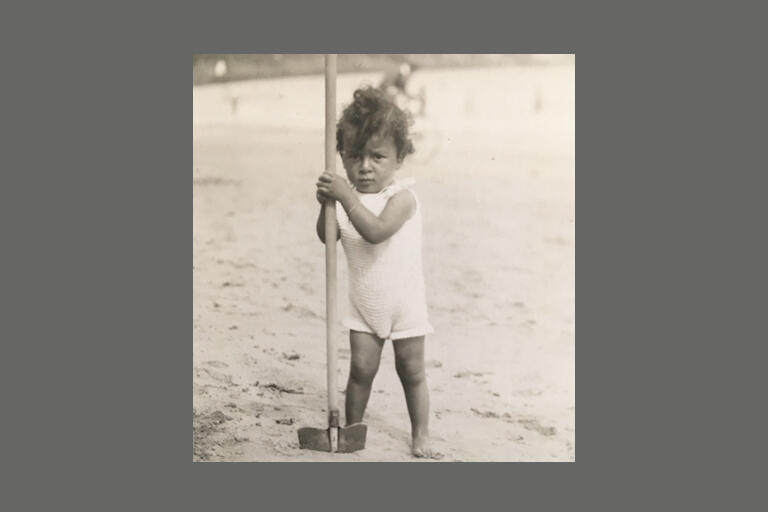

Born in 1927, Benveniste grew up in France and fled the Vichy-occupied part of the country during World War II. His father was Jewish. After moving from Paris to southern France, the family finally fled in 1942 on a boat from Lisbon bound for Mexico. Benveniste captured his earlier life in a set of digital “postcards” sent to family and friends in recent years, including former students and colleagues.

One email described how the family fled France:

We crossed the Atlantic in October 1942 on the RMS Serpa Pinto, a ship that went from Lisbon to the United States with many Jewish refugees. Before belonging to the Companhia Colonial de Navegaçao, the ship had originally belonged to the Royal Mail Steam Packet. It begun plying the sea in 1914 and was used during that First World War …. We boarded it in October 1942 in Lisbon and went first to Casablanca. I was 15 at the time and very excited by my travels. In Casablanca I negotiated with the French guard at the foot of [the] gangway to be allowed to step down all the way to the ground, place both feet on the soil and quickly climb right back. Thus, adding a whole continent to my travel repertoire. We then spent one week in Bermuda while the British searched the ship for spies or contraband. I had a great time at a party organized by the Governor of Bermuda for all the children on board.

Benveniste attended high school at the American School in Mexico City. Although his grades “were not stunning” (as he conveyed in one postcard), he was accepted at Harvard University in 1944 — believing he was admitted because his experience in the war and as a refugee were “different.” He noted that his time studying Spanish in Mexico City had improved his English.

At Harvard, Benveniste studied engineering and returned to Mexico upon graduation to work for Mexican Light and Power as a construction engineer. When “Mexlight,” as Benveniste called it in his writings, started to negotiate a deal with the World Bank, they needed his language expertise as well as his Harvard economics know-how. He was promoted to the general manager’s office. Benveniste attributed it to luck: “I happened to be at the right place at the right time.”

In 1954, he went back to the United States to work for the Stanford Research Institute, studying economic development in developing countries. He later earned his PhD in sociology and planning from Stanford.

In 1961, Benveniste was named to a task force on the reorganization of the USAID and worked in the State Department under the Kennedy Administration on cultural and educational issues. He wrote that at this time, he “morphed from construction engineer to economist” and was called to do forecasting. He got involved in the new field of the economics of education.

While working for the World Bank, he went to Afghanistan where he made one of the first low-interest loans for education. He then worked for UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, creating the UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning.

Benveniste joined the school’s faculty in 1968, bringing with him his deep knowledge of planning and organizations and his extensive international experience. His published work, informed by that experience and produced over a span of 25 years, includes Bureaucracy (1977), Professionalizing the Organization (1987), and The Twenty First Century Organization (1994).

Former students and colleagues say Benveniste’s global perspectives and experiences were invaluable to Berkeley students and the school. “All of the things he taught about policy and implementation stuck with me,” said Plecki. “I would use it in my own classes.”

She said Benveniste’s rich history, interests, and travel combined to differentiate him from other people in and out of academia. Plecki emphasized, “If Guy was anything, he was non-linear.”

Following retirement in 1993, Benveniste became a prolific painter, spending much of his later years painting at his second home in Carmel with his wife Karen. Little bought one of his paintings after a showing at Pauline’s Pizza in San Francisco, and the piece still hangs in her living room. “That painting has a wonderful sense of being in Marseille,” she said.

Benveniste kept in touch with LeCzel and Little and other colleagues through lunches at Berkeley’s Chez Panisse a few times a year.

“That was part of what rounded out his soul,” said LeCzel. “He lived a full life with jokes and beauty and good food.”

What follows are excerpts from email “postcards” that Guy Benveniste sent to friends and colleagues. The postcards are treasured by all who knew Benveniste, as they provide evocative highlights of his life spanning the 20th and 21st centuries.

MY LUCK (family history dating to the 1920s)

- My grandmother did not marry her two daughters in New York. The Sepharad Jewish community was just too small. My mother and her sister had attended the Ethical Society Fieldston School, which was located, at the time, at 33 Central Park West very near their apartment. They had no interest in the Jewish religion, in fact remained unreligious all their life.

- Two “modern” Sepharad man had to be found, who would not expect their wives to stand behind them while they ate. My grandmother first went to Dresden where luckily she married her elder daughter to a man in the import export business. She then married my mother to my father in Paris in 1926.

- These were not arranged marriages. In both cases my grandmother spent time in Dresden and then in Paris. The young women attended social events where they met young men. My mother did meet someone in Dresden but the courting did not have any final result.

- I called this card My Luck. We were lucky as my “to be” uncle in the import export business moved from Dresden to Prague. In Prague, he and his wife would have a front seat view of the German annexation of the Sudetenland in March ‘38 and the subsequent takeover of the country a year later. This is when they came through Paris with chauffeur and Tatra car and left immediately for Brazil and ultimately back to New York.

- It is my uncle and aunt who made my mother so adamant to leave. My father still had faith in the French; he even registered as a Jew in Vichy France after the 1940 defeat and the split of France into two parts. One part administered by Germany and the “unoccupied part” administered by a vassal government in Vichy. Without my aunt and uncle, I doubt I would have survived.

LYCEE BUFFON (1937-38)

- This is the annual class photo. Lycee Buffon, at the time provided both primary and secondary education. It was located on the Boulevard Pasteur in the 15th arrondissement at the border with the 7th where I lived.

- I count 41 students, which is not a small class size. In 1937-38 when the photo is taken I am in 7ieme [sic], one year before the start of secondary, therefore in 5th grade in the US system. Yes, there is a single girl. Earlier grades had a larger percentage. Since the Lycee will not admit girls in the next grade, they have been moving into girl’s schools.

- Social class distinctions are, to some extent, evident in the attire: ties and jackets for some, even one handkerchief in one jacket pocket, sweaters with or without ties for others. Most wear short pants but the boy next to the girl wears golf pants, which tended to be worn by slightly older boys.

- The second boy from the left in the top row was the bully of the class. Quite a few were excellent students. I am in the second row from the top and fifth from the left. I was always a poor student: “He will have to make a huge effort next year”. I never had a memory and French education of the time was heavily dependent on memory. Notice the array of very French faces, in many ways quite different from American boys of the period. Again, many social class distinctions are possible.

- You may notice the male teacher’s mustache. Where have you seen a similar mustache in and around 1937-38 ?

GOURMET (1939-40)

- Forget Omicron for a while. Let us recall good meals we enjoyed way back then. Way back when we were in another different kind of war. There are some good moments even in bad times like wars. My best example is that I discovered gastronomy when we fled to Pau in the south of France in 1940. When war was declared in September 1939 we first went to Vichy. My father knew the town as he used to spend two weeks there, each year, doing some heath treatment.

- But my aunt who had been in Czechoslovakia, was much more panicked and had gone to Pau to be as close to a border and away from the German border. She convinced my mother for us to join them, as there was an apartment for rent in the same building on the Boulevard des Pyrenees. We went to Pau.

- My aunt had hired a cook, a cordon bleu cook. The food I was used to was heavily influenced by my father’s cultural background. It was essentially a lower cost Mediterranean diet, where beans and ground meat had a dominant role. Suddenly, I was swimming in escalope de veau a la crème et aux champignons and finding the experience quite agreeable. This was also the food from Gascony rich in duck, foie gras, sausages and hams. From late 1939 to May 1940 I had some 6 months of Gascony cordon bleu food. I remembered d’Artagnan the Gascon of the three Musqueteers and Alexandre Dumas. It was an unexpected benefit from a bad experience.

- When I came to Berkeley in 1968, I paid attention. I remembered the Chicken a la King of Adams House at Harvard. But I was fortunate. The Chez Panisse restaurant was already here. There was a good bakery and good market. Yes, it would work. And it did.

ADJUSTING TO BOBBY SOCKS (1940s)

- I arrived in Mexico City in 1942. I went to the American School. At the time it was located at the corner of Insurgentes and Coahuila. Today, there is a huge Woolworth, one of the few still surviving, occupying the entire block.

- I came from a French Lycee, by then, devoid of feminine presence. In Mexico, I would suddenly encounter girls in the classroom. In France, we had had little girls in the primary classes; but we never had girls in skirts, bobby socks and saddle shoes. Certainly nothing like that in secondary.

- Bobby socks and saddle shoes emerged in the US at the end of the 30’s. They were at their height of popularity in ‘42 and ‘43 when Frank Sinatra drove his fans into frenzies. I arrived at the American School just in time to quickly learn how to dance and observe these fantastic phenomena: girls in bobby socks and saddle shoes walking down the corridors of the school.

- I was also quite unprepared to absorb that girls and boys seem to like each other in open ways. Sometimes holding hands while walking or even, (this was so new to me, so improbable), even exchanging furtive kisses in the back of the classroom while the teacher was writing on the board.

- We had none of that in Marechal Petain schools. We sang “Marechal nous voila” not, “you get under my skin.” I remember Ivette Delagrave and Mariana Blago walking down the halls with an escort of four football players. I remember the flouncing of the skirts and the sound of the saddle shoes.

- This was a much bigger adjustment than the shift of language. I was 15 when I arrived in ’42. I am 16 and 17 at the School. I am hitting puberty in a bang of innocence. I learned to dance, went to lots of parties where we drank coca colas and played 78’s on the record player. A parent would fetch us and we were in bed before midnight.

- It was the age of innocence and bobby socks.

NICE (1941)

- There is not much to say. We went to Nice because my father calculated that the Italians instead of the Germans might ultimately occupy Nice. It did not matter since he then dutifully registered as a Jew thus ensuring we would be arrested. He was a sticker for obeying the laws and regulations, which it turns out, is not always the smart move.

- Anyhow here are my parents on the Promenade des Anglais in Nice in 1941. Please notice my father’s suit. You can see it is too big for him. Yet he had a tailor make it before the war. He was a cloth merchant, he had all his suits made.

- He had lost considerable weight due to the restrictions and general lack of food.

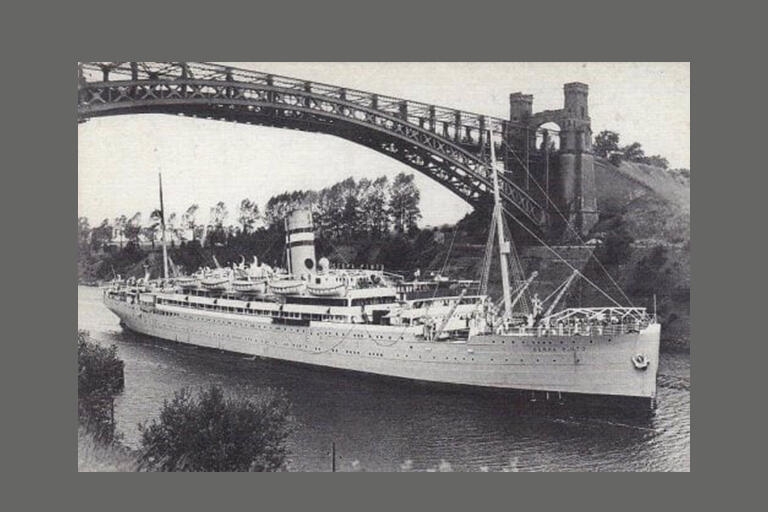

SERPA PINTO (1942)

- We crossed the Atlantic in October 1942 on the RMS Serpa Pinto a ship that went from Lisbon to the United States with many Jewish refugees. Before belonging to the Companhia Colonial de Navegaçao, the ship had originally belonged to the Royal Mail Steam Packet. It begun plying the sea in 1914, and was used during that First World War. Various companies acquired it before it become, during World War II, one of the principal escape ships between Portugal and America. It was originally the RMS Ebro and became the Serpa Pinto in 1940. The ship was scraped in 1954.

- We boarded it in October 1942 in Lisbon and went first to Casablanca. I was 15 at the time and very excited by my travels. In Casablanca I negotiated with the French guard at the foot of gangway to be allowed to step down all the way to the ground, place both feet on the soil and quickly climb right back. Thus adding a whole continent to my travel repertoire.

- We then spent one week in Bermuda while the British searched the ship for spies or contraband. I had a great time at a party organized by the Governor of Bermuda for all the children on board.

- We neared the US coast and went down towards La Habana. I saw Miami from a distance but could not really add it to the list. In La Habana port there did not seem any way to negotiate and anyhow Cuba was part of America and we were going to Mexico, there was no real need for Cuba on my list. In addition the Cubans seemed to wear shirts outside of their pants, which seemed very strange to us Europeans. Why could they not tuck them like everyone else?

- We then went toward Veracruz. One morning there was a cry: Land! We all looked and sure enough, sticking out of the sea, was the top of the Orizaba Mountain, like a small cake on a vast blue sauce.

- The trip took a month. I spent most of those days at the very top of the ship in the code room helping send Morse code messages. I was a boy scout who knew the Morse code. I can only do S O S now: …_ _ _...

- My mother did not like Veracruz but she calmed down when she saw the Avenida de La Reforma in Mexico City. It was more like Paris.

- My parents and I were quite happy to be leaving. We did not know much about what was happening, but we knew enough to want to leave as quickly as possible. We left France in May and boarded the Serpa Pinto in October. I spent that time at the Carcavelos School for Boys where I learned English and played cricket. Obviously, it was a happy time, one was escaping the dangers of Europe.

MY WAR (1940 and 2022)

- In 1940 I am 13. My war was one of armies fighting each other. Hitler wanted an intact Paris, so it was never bombed. France surrendered in June 1940. London in contrast was heavily bombed during the “Blitz” from September 1940 to May of the next year. London was saved when Hitler began his war against Russia. But while the Blitz was indiscriminate, there was none of the detailed nastiness we now witness. In that sense it was a war of armies, bombers in the dark dumping loads of bombs.

- I would say that the war in Ukraine is not a war of armies. It is an especially nasty war of one army against one people. A war where hospitals, schools and churches become desirable targets, a much higher level of inhumanity.

- The US was “neutral” during the Blitz just like we will not even declare a no flight zone today. Does Putin have to invade Alaska? Is this the new Pearl Harbor?

by Guy Benveniste