It started as a casual meet-up at a downtown Berkeley cafe. Professor Dor Abrahamson planned to do a little humble bragging with his latest tablet app, the Mathematics Imagery Trainer, designed for middle schoolers to learn ratio and proportions, which he'd rigged up to include beeping noises for sight-impaired students.

Within minutes of his conversation with Engineering PhD Josh, it was Professor Abrahamson who was humbled.

In that 30-minute exchange, Professor Abrahamson's 20+ years of educational theory flashed before his very eyes. And then he found an opportunity.

Read below as Professor Abrahamson recounts the intriguing origin story of The Quad, a hand-held, versatile quadrilateral that, when blue-toothed to a computer, allows sighted and sight-impaired students to learn geometry — together.

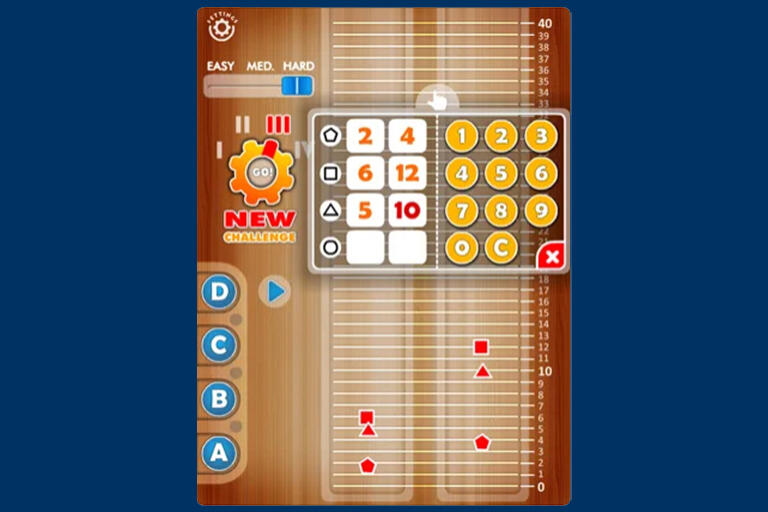

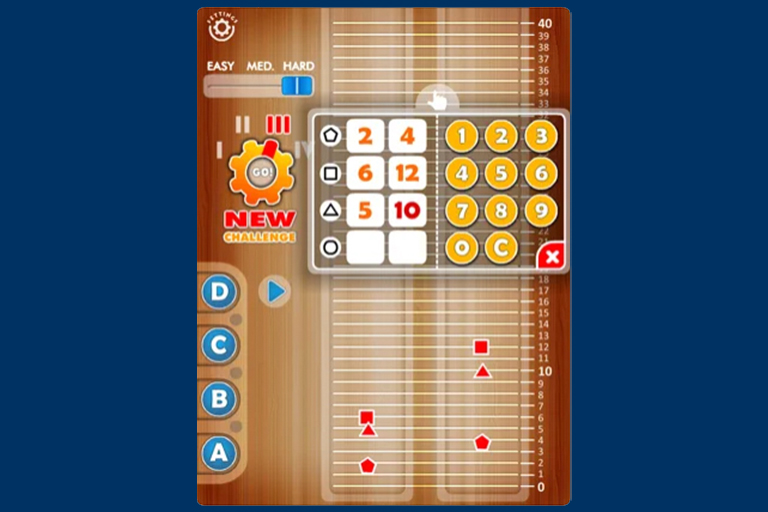

I was both mortified and inspired, one Tuesday, back in September, 2017, when Josh and I met for coffee at Au Coquelet Café on the corner of Milvia St. and University Avenue. Josh is an engineer, a Berkeley PhD in psychoacoustics, and an inventor of technological solutions for blind professionals to manage complex quantitative data sets. I was presenting to Josh a tablet app I had designed for kids to learn the math concept of ratio and proportions, such as 2:3 = 4:6. In this app, you slide your two index fingers, the left and the right, up along the interface at different speeds. If you move them at the correct speeds relative to each other, so that they are always 2 and 3 units above the bottom line, respectively, the screen will be green.

But green doesn’t mean too much for Josh, who is blind, and so I proudly switched on the alternative sound feedback, a semi-pleasant beep. I watched Josh work. Indeed, he slid his fingers up the screen, seeking the beep. But he also did something else that I had not seen anyone do before, and this after ten years of developing this activity, using mechanical pullies, Wii-mote, Kinect, and LeapMotion remote sensors, mouse, trackpad and, now, tablet: Josh used his thumbs, too: he looped each thumb around the tablet’s exterior encasing, even as he slid the index up. Now why would he do that?

“Why are you using your thumbs, Josh?” It was truly mysterious to me. It appeared contrived, contorted, and darn right confusing. “Well,” he retorted, a tad bemused, “If I don’t keep my thumbs down there as I move my indexes up here, how will I know where I am? How would I gauge the ratio of these two gaps? I’m blind, Dor. Hello?” I was mortified.

Mortified, because Josh was stating the obvious. “You, sighted people,” Josh went on, “You go on and on about visual this and visual that. But vision is not the thing itself, it’s just a way of getting at the thing itself—what counts is space, the spatial arrangements of stuff in the world. I can’t see, but I know what things are and where things are. I feel, I hear, I can get from place to place. Vision is just one conduit for the real thing, which is actually the size and place of things. It’s about spatial relations, like in this app.” And the app beeped, a nice continuous semi-pleasant triumphant beep. Fifteen–love.