It has been two generations since the Education Amendments of 1972 were signed into law, which includes the landmark Title IX, designed to bring gender equity at educational institutions that receive federal funding.

Van Rheenen is a critical studies scholar who examines sport as political struggle and how it both influences, and is influenced by, historical patterns of alienation, discrimination, and inequity in schools and our broader society.

His research is also partly informed by personal experiences. Born in Nigeria and raised in California, Van Rheenen played professional soccer and was a student athlete at Berkeley. He earned his bachelor’s in Political Economy and German, master’s in education, and PhD in cultural studies from Berkeley. His critical perspective examines how sports, beyond the physical and mental health benefits for athletes, and aside from its entertainment and business value, are often grounded within the dominant interests of the wider community. In this context, sports are not immune to social divisions inherent to reigning race, class and gender relations.

Cutting across all of his research projects is a passion for cultural critique and a corresponding commitment to social change.

Van Rheenen calls himself hopeful, even utopian, as he envisions sport as a potential platform for social and environmental justice and activism.

Van Rheenen’s paper chronicles the game preferences of American children during the twentieth century, documenting the results from four studies between 1898 and 1998. Findings revealed that the game preferences of boys and girls have become markedly more similar over the course of the 20th century.

In fact, seven of the ten favorite activities self-reported by girls were shared by boys. These activities included basketball (#1 for boys, #3 for girls), computer games (B #2, G #7), soccer (B #5, G #5), swimming (B #6, G #1), tennis (B #8, G #9), bike riding (B #9, G #10), and cards (B #10, G #8). This similarity between the genders in their reported game preference was particularly striking as these activities were selected from a list of 190 games and activities.

The dominance of sports and electronic (computer and video) games at the end of the 20th century not only reflected the technological advances of American society; it also indicated an increased desire for games that demand greater skill and promote role specialization.

As Van Rheenen argues, “the shift in game preferences to skilled, organized, and adult-supervised activities and the erosion of gender-specific game activities are two of the most resonant themes from this comparative study. Taken together, they suggest that the gender divide among children has become less marked or institutionalized within American society” (411).

Van Rheenen’s work challenges the idea that there exist “boy’s” and “girl’s” game. Hopscotch, for example, perceived within the mid- to late- twentieth century to be a “game for girls” was similarly regarded as a “game for boys” throughout the seventeenth, eighteenth, and most of the nineteenth centuries. As such, findings that report seemingly “natural differences” between the sexes based upon play preferences more likely reflect the cultural construction of gender at a particular historical moment.

Despite the increased similarity between the sexes in game preferences over the course of the twentieth century, it would be misleading to assert that children’s games have become gender neutral. Chi-square analyses revealed significant statistical differences (p < 0.01) in the frequency of response among boys and girls on several activities. In particular, at the turn of the twenty-first century, boys preferred computer and video games, football, baseball, and wrestling, while girls preferred dolls, dance, jump rope, hopscotch, and drama.

However, the most striking result of the twentieth century in terms of children’s play patterns has been the convergence, rather than the disparity, among the sexes in their game preferences.

Van Rheenen: I think more, now more than ever, in a post pandemic, postmodern world, traditional signifiers like gender have become conflicted and highly politicized terrain. It is not only scholars and artists who intentionally challenge or question the status quo by deconstructing primary binaries like male/female and the dominant ideologies and structures that inform these social and historical constructions; what may have seemed ... Read more.

an intellectual abstraction or “radical” social movement decades ago has become a lived experience for many, a more open social reality, where young folks and old alike don’t want to be labeled or defined. They seek a more fluid world, where they can be anything they want to be, a shifting landscape of self expression. But this freedom of expression scares many people.

As we are witnessing today, there is an intentional effort to reify, codify and return to more rigid understandings and boundaries connected to gender, often claimed to promote traditional values and “natural” readings of sex, gender and the body politic. It is a very intentional effort to close Pandora’s box.

Gender (like other social and historical constructions) is a conflicted terrain. But the stakes are high, very different worlds envisioned before us.

There is a fight for control of our minds and bodies inside and outside of schools, as evidenced by recent school board decisions, court rulings and political platforms promoting misogyny, homophobia and transphobia, not to mention an assault on our democracy and our freedom of expression more broadly, such as banning books on critical race theory and anything deemed different or “queer.”

In my view, we are embarking on a dystopian future rather than a world that is inclusive and compassionate. Call me crazy, call me woke (I am a Berkeley professor after all!), but I envision one world for all and not just the few, a minority who seeks to maintain power and privilege at the expense of other people's lives and their dignity.

Van Rheenen: There is an interesting evolution in girls’ foray into modern games, and I would say one of the most profound shifts since the early 1970s is in games that kids prefer to play. Think about it: in 1971, just one out of every 27 varsity high school athletes was female; when I wrote the article ten years ago, it was one in three. Now, girls make up more than 4 out of every 10 American high school athletes. That’s phenomenal! Read more.

My research examines Title IX and the societal shifts related, at least in part, to this landmark legislation.

Since the passage of Title IX of the Education Amendment in 1972, the increased interest and ability of girls to participate in institutional games or sports has been striking. For example, the number of girls playing varsity high school sports increased from 295,000 in 1971 to about 3.06 million in 2008, more than a 1,000 percent increase.This dramatic shift in game preferences has coincided with the Women’s Movement and gender equity as a legally mandated and viable cultural expectation. The number of women in the workforce has markedly increased over the course of the twentieth and well into the twenty-first century. Women are leaders of industry and social changemakers, CEOs and cultural influencers.

These societal shifts have challenged the common patriarchal notion of the nuclear family, having the father of a two-parent, heterosexual household as the solitary breadwinner in the family. American families are diverse. Love is not limited to a traditional recipe. There are many ways to raise our children and to live together, many ways to care for and love one another.

What's important to note, however, is that as girls began to prefer more organized and active games, perhaps reflective of the greater social mobility of twentieth-century women, boys shifted their preference for games with ever heightened activity—games characterized by enhanced speed, aggression, and role specialization. This shift has coincided with a marked increase in the popularity of major sports, particularly aggressive, even violent, team sports, such as football, basketball, and soccer. Mariah Burton Nelson’s classic book in the beginning of the twenty-first century, The Stronger Women Become, the More Men Love Football (2001), captures this historical development well.

Van Rheenen: There are a lot of anniversaries at this time and, together, they say a lot about American culture and our campus as a reflection of the historical trends relative to shifting gender relations, particularly as it relates to sport, culture and education. In 2018, Berkeley celebrated its 150th anniversary as the premier public university in the United States. The first class was composed of 40 young men and ten faculty members. Read more.

The university began admitting women the following year.

This year we celebrate the 125th anniversary of the Big Game, the iconic American football match pitting California against Stanford University. It is a celebration of our tradition as a campus, an institutional rivalry that promotes Golden Bear pride but also dominant forms of masculinity.

It is worth noting that the inaugural Big Game was played in 1892 (a few years games were not played or not considered official over the past three centuries). Less known is that the first documented women’s intercollegiate athletic event in the United States (above image) was played in 1896, a basketball game also between Cal and Stanford. Spoiler alert: we lost 2 to 1.

We also celebrate 100 national team championships at Berkeley this year. The disparity between men’s and women’s national championships tells the tale of historical gender inequity. Berkeley has earned 89 men’s national championships and only 11 women’s honors, the first in 1980, eight years after the passage of Title IX. The next women’s national championship was not until 2002.

The premise of Title IX is that the interests and abilities of the minority sex should be protected within American educational institutions as a mechanism to combat historical exclusion from school and sport. But it’s a double-edged sword, because historical exclusion stymies the development of interests (we are socialized to acquire particular tastes and preferences) and corresponding abilities. You can’t get better at something you do not do (or have the opportunity to do).

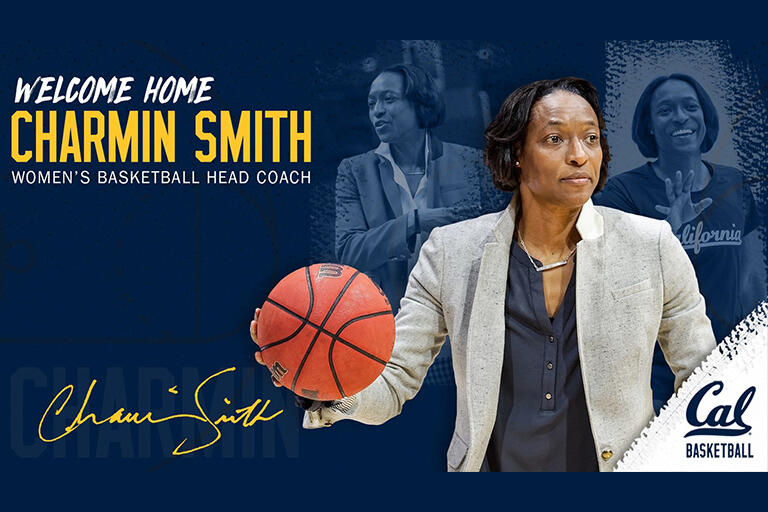

UC Berkeley’s story of the uneven development of women’s sports and American higher education is similar to the national narrative. Women’s college sports were originally organized and governed by women, for women. The passage of Title IX actually led to the elimination of, or reduction in, women’s distinct athletic departments and national governing bodies, female administrators and female head coaches. As women’s sports gained in cultural and institutional viability (promoted by legal mandate), men took over control of sport in American schools.

The more popular, public narrative is that Title IX has led to the elimination of men’s athletic opportunities and men’s varsity sports programs (and that has happened); but it is a far more complicated story than pitting female athletes and women’s sports against non-revenue (e.g., Olympic) male athletes and sport programs against one another. I have written about this as well, “The Elimination of Varsity Sports at a Division I Institution.”

Van Rheenen: We definitely need Title IX. Sadly, there is little cultural imperative for equity based on moral or ethical grounds. The legal system is cumbersome and fraught with challenges, but it is our best vehicle at this point. And, there are at least some sharp teeth to ensure progress or forestall the backlash to preserve existing structures of dominance (e.g., male hegemony). Read more.

But, our legal system is also under assault, one aspect of democracy’s checks and balances, in favor of a particular ideology.

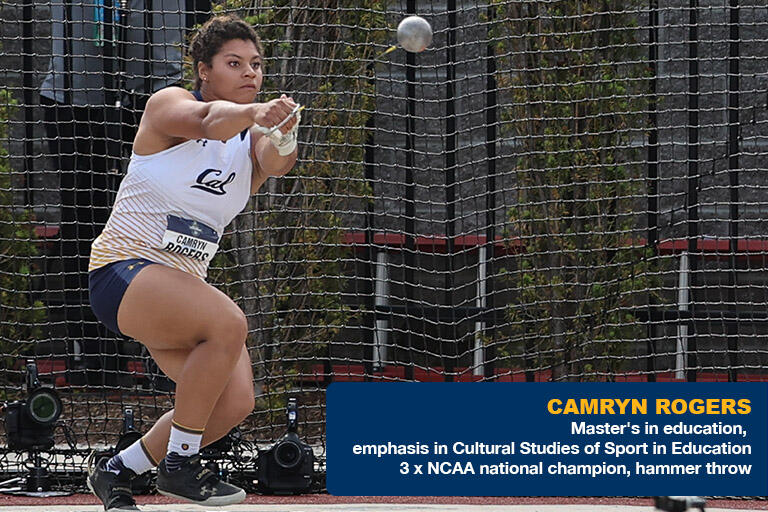

Landmark legislation, such as Title IX, takes time to witness lasting social change. But we are beginning to see the benefits of this historical piece of legislation. In this year’s cohort of the Cultural Studies of Sport in Education (CSSE) MA concentration within the BSE, the majority of new graduate students are women, all of them elite, Division I scholar athletes. These strong women represent Berkeley’s varsity teams in basketball, track and field, softball, soccer and beach volleyball.

They are a product of our time, recipients of cultural progress in terms of gender equity in youth, college and even professional sports. They are also changemakers in their own right, pushing boundaries and expanding definitions of gender as non-binary and fluid, a more open terrain of self-expression.

Modern sport offers us a glimpse into cultural reproduction and resistance. In a relative blink of time, Title IX is a recent phenomenon, an exclamation point and moment of social progress. There is pressure these days to overturn women’s rights, LGBTQ+ rights and limit free speech.

And we still have a ways to go relative to global gender equity. Five of the world's most populous countries, China, Nigeria, Russia, Mexico, and the United States, have never elected a woman leader.

There has been a corresponding call to empower women and other historically marginalized groups, to save Mother Earth and remedy the current course of human civilization ("Nature Sports: Prospects for Sustainability"). That may seem hyperbolic, but the stakes are exceedingly high. The Berkeley School of Education is firmly in this fight for positive change.

For me, I opt for a utopian vision of the world, one that intentionally includes rather than divides. As an educator and global citizen, I have faith in humanity, our youth and our future.

We should all be celebrating the 50th anniversary of Title IX. Fiat Lux, and Go Bears!

Oh, and we need a female president in this country!

Derek Van Rheenen’s research interests include the cultural studies of sport, nature sports, sport tourism, ecopedagogy, the connections between sports, learning and schooling, and the role of intercollegiate athletics in the American university system. A former Academic All-American and professional soccer player, Van Rheenen teaches courses on sport, culture, and education. In 1998 he received the Outstanding Dissertation Award in the School of Education. Van Rheenen has also been named a Chancellor's Public Scholar. In 2022, he was promoted to full adjuct professor. Read more.

He is the Faculty Coordinator of the BSE-wide MA Program and the Faculty Director of the Cultural Studies of Sport in Education (CSSE) Master's degree specialization for students studying the intersections of school and sport. He has also been the Executive Director of the Athletic Study Center at UC Berkeley since 2001.

Van Rheenen has been a Visiting Professor at the University of Lille and the International University of Monaco, is an invited speaker at national and international conferences, and is regularly interviewed about the role of sport in society and the intersections of sport and schooling, particularly American college sports.

While most of the public attention on Title IX has been focused on athletics, the law is much broader. Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 prohibits sex discrimination (including pregnancy, sexual orientation, and gender identity) in any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance. Below are some additional resources. Read more.

An overview of Title IX

Full text of Title IX

University of California, Systemwide Title IX Office

National Center for Education Statistics, Fast Facts on Title IX

Panel Discussion: Title IX at 50 - Looking Back, Looking Forward